One of the first rules of big data, could quite possibly be the following: there is no Big Data. That is – there is no single piece of big data research that is definitive. A research that gives you completely conclusive results, a research that does not generalize, a research piece that will be relevant in its entirety the next day after it has been drafted. However, don’t take this personally. Big data doesn’t have anything to do with you. Nor with any real person.

One of the first rules of big data, could quite possibly be the following: there is no Big Data. That is – there is no single piece of big data research that is definitive. A research that gives you completely conclusive results, a research that does not generalize, a research piece that will be relevant in its entirety the next day after it has been drafted. However, don’t take this personally. Big data doesn’t have anything to do with you. Nor with any real person.

Big data is a synthesis of the average John Doe. Big Data looks at human communities, human interactions, and human behavior on an extremely large scale. Therefore, like in a photograph, the farther away you take this picture from, the more indistinguishable the distinctive traits of John will be. And unless your camera has the megapixel muscles of the Hubble Space Telescope, zooming in will only give you a faint outline of that person.

To get in touch with trends, therefore, big data uses highly advanced programming codes that analyze results over longer periods of time. The shorter the time, the more inconclusive the results. For instance, basic algorithms may be confused by the fact that our hypothetical John likes to work from a different place each day. More complex big data analytics would find a pattern in this, and would mix in John’s taste in music, drinks, books, etc. with John’s usual suspects when it comes to hanging out. It would thus make a list of all the probable places John would like to work and compare the results to the places he’s actually visited in the past. Then, it could make a fairly reasonable assumption on where John is on any day of the week.

This all seems very creepy when we think of John alone, poor guy. But what I’ve said here to be John, is actually the worst scenario for big data analysts. And it’s perfectly doable, it just takes inhuman amount of research. The actual case is that there are thousands, sometimes millions of Johns. And these Johns don’t like to confuse big data. They don’t go to a different place every day. That’s because peoples’ brains also like orderly behavior. The feeling of security that going to work every day gives you.

It doesn’t take big data to predict that a big group of people will be passing through the London Underground at 8 AM each morning. However, big data could be useful when it comes to observing differences or slow shifts in these patterns. This, in turn, helps targeted advertising, emergency units, secret services, and not only. These three all maintain order within a society, and are, surprisingly, equally efficient.

One instance of how big data is used productively is when it monitors crime rates in respect to road changes. Or how the changing metropolis influences people into buying houses in different areas, how it impacts their spending habits, or how likely it is that there will be instances of burglary in their new neighborhood.

Fitting the Sims into the Equation

Recent big data analysts have begun using city simulators like The Sims or Sim City. The underlying concepts between both these two games have done something very right in an area where big data has traditionally failed. That is: metaphorically imagining a city. Simulators such as The Sims and Sim City both let the user go about building their city very much like an organism. Big data, given its analytical nature, has for years assumed the contrary: that the city is a machine. In this machine, everything was manufactured by everything people experienced. The inner workings were thought to be complex, but not as complex as in an organism.

It turns out that the people who came up with that idea were on a different plain from the truth. In actual fact, humans are largely unpredictable. You can tell what a group will do from time to time, but there’s always a little hint of serendipity that could dismiss any assumption. In a stranger-than-fiction manner, as much as people like routine, people also like altering this routine. So – there is a natural margin for error that goes into any big data analysis, much like in theoretical physics.

Fitting Social Media into the Equation

To make up for this error margin, recent times have seen big data using social media. After all – as some have pointed out, people readily make available personal data about their preferences, their preferred places to spend time, and even their home. Furthermore – people even give consent to big data using their info, and worst of all: they don’t even understand what they’re accepting.

Thus we are entering into the ethical dilemmas that are naturally involved when talking about big data and social media. Let us return to John Doe, see what he’s been up to:

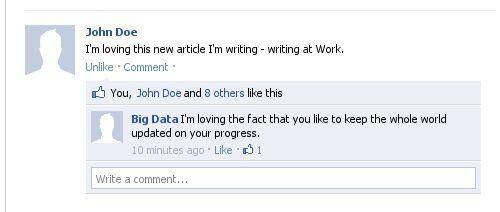

Well, since we’ve left him in the London Underground, John has been very busy. After leaving the subway, he saw how lovely the sunrise was showing and decided to take a picture and post it on Instagram. When he opened the Instagram app, his location was scanned – something he consented to when he downloaded it. He then got to work, where he posted to Facebook something along the lines of:

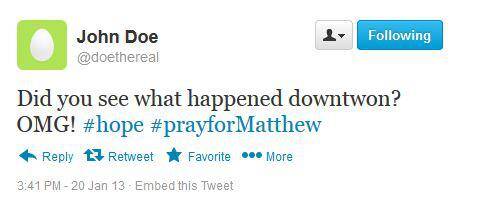

Then, he goes out to grab something to eat at about 2 PM. On his way to wherever he’s going, he comes across a great crowd of people. There was a terrifying accident and everybody is Tweeting about it, even John:

Of course, by the end of the day John Doe will have visited a lot of places. And these pieces of info will prove incredibly useful for big data analysis. While the Instagram post will serve as a key point of reference to John’s whereabouts at that point in time, the Facebook post will let the whole world that he was at work at the time. The trail of check-in locations doesn’t even need John’s actual check-ins. Provided John clicked a lot of “accept” where he could’ve picked “deny” – all or most of the apps he opens on his smartphone will tag his location at that precise moment in time.

The Twitter post is even more conclusive for big data. The fact that John and many other people present at the scene have used “#prayforMatthew” will make it a trending topic. Thus, it will be seen by more and more and more people. In this group of people will probably be journalists who have their fingers ready to score another viral article.

I know this seems incredibly cold for poor Matthew, but we must be realistic: there are the ways – or at least some of the ways – in which big data works. It’s all part of the living organism we call urban society. And the thing is: with 66% of the people on Earth living in cities by 2050, big data is not only a good thing to have – it’s necessary.