With online data acquisition on the rise, we are treading into mostly uncharted waters. Industry-wide regulations in web scraping and other forms of automated data collection are practically non-existent and we probably shouldn?t expect any in the near future. However, there are a sufficient number of other pointers that can help us stay on the right side of the law and ethics.

Apart from specific legal cases where web scraping has been raised into question, we should look towards the type and form of the data itself. There are several ways to categorize online data although I will be separating them into 3 primary types: public, non-public, and personal data.

(Non-)Public data

While landing upon a clear-cut definition of public data might be difficult, US case-law might give us a good glimpse into what it might look like. Back in 2019, the US Court of Appeals had denied LinkedIn the request of preventing HiQ, an analytics company, from scraping its data. The court found that HiQ managed to show a likelihood of success on the merits of its claim that automated data collection of public data does not fall under the access ?without authorization? prohibition established in the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).

Most importantly, the court assessed that the data that was accessed by HiQ labs could?ve been accessed by anyone with a regular web browser and, in my opinion, believed that the entry of a scraping robot (when accessing public data) is not any different than to that of any other web browser done used by human. That brings us an additional argument – automated public data collection shouldn’t be held as something different than manual collection is, it is just a smart and more efficient way of doing things.

However, the US Court of Appeals does not open the gates to absolutely any type of online data collection. While it may be obvious, it needs to be stated that a lot of legal statutes and legal arguments for defence, such as copyright law, database protection rights, breach of agreement, etc, remain in place. For example, usually copyrighted data (or content in general) cannot be collected and used for commercial purposes.

As mentioned, the ruling does not override Terms and Conditions. Wherever a log-in or registration is required, you would probably have to agree to T&C before being able to scrape the website in question. What is more important, such data could probably be classified as non-public from that moment on. In nearly all cases, websites will forbid any automated data collection.

Therefore, public data might be defined as freely available informationthat can be accessed without signing Terms and Conditions or other legally binding documents. We consider everything else as non-public data that, if other legal arguments are not enacted, can be gathered using automated means.

Personal data in the EU

Instead of thinking of personal data as a different category altogether, we might think of it as an additional dimension. All of online information can be separated into public and non-public. Some of both categories will be personal data.

One of the foundational legal sources for understanding the concept of personal data is the much-maligned General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). While businesses that deal in exclusively non-EU data and are not established in the EU might be exempt from GDPR, in nearly all cases such a separation is nigh-on-impossible. Therefore, everyone might as well follow GDPR regulations.

Luckily for us, there is a very exact definition of what constitutes personal data in Article 4 of GDPR:

?Personal data? means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (?data subject?); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person;

There are several important take-home notes included in the definition. Any data that might directly or indirectly identify or add to the identification of a person or any of his qualities is considered personal. Such a definition casts a very wide net on what might be considered personal data.

For example, even information that may seem innocuous like height, weight or even the color of a person?s car may be considered personal data. Additionally, there may be cases where non-identifying data points merge to an identifying set. These situations generally involve some minimal tracking (e.g. a generic geographical pointer) and behavioral information (e.g. a set of commonly visited locations).

Under GDPR, private data can only be processed if there is a legitimate legal basis for such processing. Realistically, receiving the consent of every person involved in data acquisition is only possible in internal collection processes. For external data acquisition (e.g. web scraping) such a task is if not at all impossible, at least extremely impractical. Additionally, GDPR defines several special categories of personal data that may include:

- Racial or ethnic origin

- Political opinions

- Religious or philosophical beliefs

- Trade union membership

- Genetic data

- Biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person

- Data concerning health or a natural person?s sex life and/or sexual orientation

Finally, GDPR defines ?online identifiers? as part of personal data. These are provided by user devices, applications, tools and protocols which may identify persons. Examples of online identifiers may include: IP & MAC addresses, cookies, radio frequency identification tags, etc.

Collection of sensitive personal data is subject to even more rules and regulations. In practice, all of these roadblocks mean that GDPR puts a heavy burden on scraping personal data.

Personal information in the US

There doesn?t seem to be a lot of hope for personal data collection in the EU. What about the US? There is no federal-level legislation on personal information, however, state-level laws have been introduced.

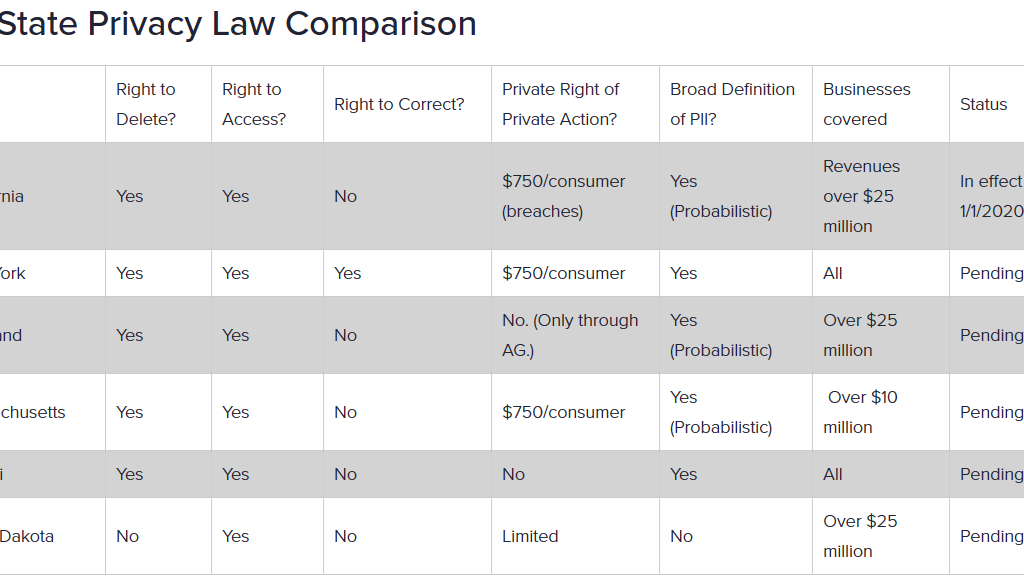

As of 2021, only several states (i.e. California, Virginia. Vermont has a data broker law) have introduced legislation targeting personal information. However, going through all of these laws in detail would take a considerable amount of time. I will be tackling the root piece of legislation as most of these laws are more or less extensive copycats of the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA).

CCPA is the most widely cited piece of legislation when it comes to personal information. However, a large portion of the legislation is dedicated to providing consumers with the right to know, access, opt-out, or outright delete the data collected. Pragmatically, these cases will generally involve internal data collection within businesses.

Just like within GDPR, the personal information definition included in CCPA is quite expansive:

Personal information? means information that identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household. Personal information includes, but is not limited to, the following if it identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could be reasonably linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household.

For simplicity?s sake, everything that is considered personal data under GDPR falls under CCPA as well. There?s an important caveat, though. CCPA includes a definition for ?probabilistic identifiers?:

?Probabilistic identifier? means the identification of a consumer or a device to a degree of certainty of more probable than not based on any categories of personal information included in, or similar to, the categories enumerated in the definition of personal information.

In practice, probabilistic identifiers come close to the identifying datasets I have mentioned previously under GDPR. In most cases, one data point that is not personal information will also not serve as a probabilistic identifier. However, several data points that are not identifying by themselves combined in one dataset might become a probabilistic identifier.

There is one important difference in CCPA – consent is not mentioned directly. If the data collected is intended for sale, each person whose data has been acquired needs to be informed. Additionally, the notice has to be provided ?at collection?. In practice, this often means that automated data collection for explicitly commercial purposes is, yet again, impractical.

Conclusion

Consumer privacy and data ethics legislation is on the rise and with good reason. Unfettered power in data collection can definitely lead to misuse. We are at the humble beginnings of widespread use of web scraping and, yet, we can already see its incredible potential.

By understanding the types of data in existence, we can clearly delimit what is fair game for web scraping. After that, maintaining the highest standards of ethics will be a piece of cake.

Tagline: It is important to understand the different types of online data if you want to implement a successful big data strategy.