Business planning as practiced today is a relic, a process hemmed in by obsolete conceptions of what it should be. I use the term “business planning” to encompass all of the forward-looking activities in which companies routinely engage, including, for example, sales, production and head-count planning as well as budgeting. Companies need to take a fresh view of all these, adopting a new approach to business planning that while preserving continuity makes a substantial departure from what most companies do now.

Business planning as practiced today is a relic, a process hemmed in by obsolete conceptions of what it should be. I use the term “business planning” to encompass all of the forward-looking activities in which companies routinely engage, including, for example, sales, production and head-count planning as well as budgeting. Companies need to take a fresh view of all these, adopting a new approach to business planning that while preserving continuity makes a substantial departure from what most companies do now. Currently, in most organizations the budget is the only companywide business plan. However, while necessary for financial management and control, budgets are not especially useful for running an organization.

Individual business units make plans, but they are narrowly focused and not well integrated with other parts of the organization. That means companywide efforts are not as coordinated as they could be: Just 22 percent of the participants in our integrated business planning benchmark research said they can accurately measure the impact of their plan on other parts of the business.

integrated with other parts of the organization. That means companywide efforts are not as coordinated as they could be: Just 22 percent of the participants in our integrated business planning benchmark research said they can accurately measure the impact of their plan on other parts of the business.

While today’s budgeting and operational planning efforts are loosely connected, the next generation of business planning closely integrates unit-level operational plans with financial planning. At the corporate level, it shifts the emphasis from financial budgeting to business planning and performance reviews that integrate both operational and financial measures. This new approach uses available information technology to enable businesses to plan faster, with less effort, while achieving greater accuracy and agility.

We have identified four characteristics that the next generation of business planning must have to help a company improve competitiveness. First, it must be performance-focused, measuring results against both business and financial objectives. Second, it must help executives and managers quickly and intelligently assess a range of contingencies and tradeoffs to support their decisions. Third, it must enable all individual business planning groups to work in a single, central system that can simplify the integration of all the plans into a single view of the company, as well as make it easy for planners in one part of the business to see what others are projecting. Our business planning research found that just 27 percent of midsize and larger companies directly link their individual plans to their budgets. Those that have such links are much more often able to drill down into underlying details while reviewing performance than those having indirect or no links. Moreover, they more often have more accurate financial plans than those that summarize information or have no links at all. Fourth, the next generation of business planning must be efficient in its use of people’s time. Success in business stems more from doing than from planning. Timeliness contributes to agility, especially in larger organizations. Today’s business planning isn’t completely at odds with this description, but in practice it falls short – often considerably.

At the corporate level, businesses need to plan and they need to budget. Today, almost all companies conflate the two into a single process that I call “budgetingandplanning” because it homogenizes the things that concern operating executives and managers (for instance, units of production, sales calls and head count) with the financial consequences of those things (cost of sales, travel and employee expense). In the long run, this is not helpful. It’s important to understand the financial consequences of any plan, but looking at “the numbers” in purely financial terms rather than being able to examine each element separately diminishes clarity. For example, is the gross margin wider because of better-than-expected pricing, a lower-than-assumed scrap rate, inventory accounting adjustments, some combination of these factors or something else? Lumping them together won’t tell you, and on the technology side using desktop spreadsheets makes it too difficult to keep the things and the money separate; the result is budgetingandplanning. As well, since most of today’s corporate planning distills forecasts and actual results into financial terms, it makes the process budget-centric, not business-centric. Individual business units create plans and review results in terms that are meaningful to them, but these are usually stand-alone efforts that are not well integrated. For that reason, nine out of 10 companies in our research reported that they experience a lack of coordination between departments, and 42 percent said it happens frequently.

The next generation of business planning untangles budgeting and planning. Although the terms are often used interchangeably (especially in finance departments), the activities are different. The object of budgeting is control, a way of constraining spending to ensure that a company doesn’t fail. The object of planning is to succeed. Whether it’s a shop-floor production plan, an R&D plan, a sales plan or what have you, planning lays out business objectives and the methods and resources necessary to achieve them. It’s the process of determining, for instance, how best to manufacture the needed mix of products, get new products on the shelves or assign territories and quotas to ensure that sales and market-share objectives are met. For its part, budgeting sets fixed financial targets for the purpose of control. Yet business exists in a dynamic world. To be successful, plans must constantly adapt to changing conditions. The two processes are interrelated, but they are not the same. Used properly, today’s planning software makes it possible to manage both on parallel tracks, shifting the emphasis to business planning and simplifying the construction of the budget.

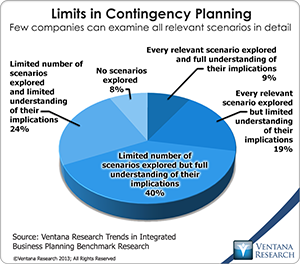

To be effective, business planning also must be a structured dialogue. Structure means that there are concrete measures involved (“Our objective is to increase market share two percentage points.”) rather than general assertions (“We plan to sell more.”). The dialogue aims to set and achieve specific business goals – a mix of quantifiable objectives related to, for example, customers, markets, operations and finance. Such dialogues must be iterative, an exchange of information and perspectives that explore what’s feasible and the trade-offs that are inherent in any business decision-making process. Since conditions are constantly in flux, business planning must consider alternative outcomes (positive and negative) and what to do about them, also in a structured fashion. Having a structured dialogue about the consequences of different outcomes requires an ability to do quantifiable what-if planning: What happens to revenue, costs, market share and so on under scenario A as opposed to scenarios B, C and D? Today, however, only 29 percent of companies are able to assess every relevant scenario and only 9 percent are able to do so in detail, our research shows. And businesses have internally competing interests. In evaluating plans,  executives should be able to determine how best to set objectives and apportion resources, ideally by quantitatively assessing the business impact of different sets of plans to find the best fit for the circumstances.

executives should be able to determine how best to set objectives and apportion resources, ideally by quantitatively assessing the business impact of different sets of plans to find the best fit for the circumstances.

Today’s planning software makes it easier than ever to perform multiple iterations, which is impossible to achieve using desktop spreadsheets. With in-memory systems, it is possible to consider the impact of multiple scenarios and compare outcomes side by side in minutes rather than hours or days, even with complex models utilizing very large data sets and even big data. With large data sets comes the ability to utilize predictive analytics as a planning tool. Despite its name, predictive analytics is useful for more than making more accurate forecasts. It also makes it possible to spot divergences from a plan almost immediately as opposed to waiting for the end of a period to review results. Executives and managers can be alerted faster when unexpected opportunities and threats arise.

In the past, financial data was more readily available than operating information. Manual systems and desktop spreadsheets made it too time-consuming to integrate operational and financial data in individual plans into a single view of an organization. For these reasons, it was practical to take a budget-centric approach to business planning and focus on financial data and metrics. Today, however, information technology makes gathering a wider range of operating, financial and external data far easier. Off-the-shelf applications reduce the difficulty of constructing models based on key performance metrics. These can deliver operations and finance perspectives in parallel to satisfy the full set of management needs. Our research finds that in a range of planning activities such as budgeting, sales planning, compensation planning, and sales and operations planning, approximately two-thirds of users of dedicated applications said their software performed these tasks well or very well, compared with just one-third of those who used desktop spreadsheets.

I recently had dialogue with a large publicly traded company that had never had a formal corporate budget. Its new CFO felt one was necessary. Unfettered by history, the company made the budget a simple extension of its existing planning process, choosing a dedicated application that would allow managers to continue planning the way they always had but also enable Finance to quickly construct a budget and periodic reforecasts from those plans. This is the essence of the next generation of business planning. It need not be an especially complex process.

For decades, just about everyone has been griping about budgeting. Decades’ worth of books, articles and blogs have catalogued its many deficiencies. As well, Ventana Research has conducted extensive benchmark research to examine the issues affecting today’s approach to planning and budgeting and its impact on corporate performance, finding that despite its deficiencies, traditional budgeting has changed little in most companies. However, a new generation of business leaders is beginning to take control of companies and their finance departments as baby boomers retire. This new generation has different expectations about what technology can and should do. These business leaders are more likely to be dissatisfied with the status quo and more open to using technology to redefine and redesign the next generation of business planning in their organizations.