Recently I saw an example where a “good enough” data design, similar to the one pictured, enabled a significant application bug.

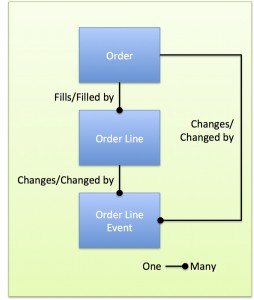

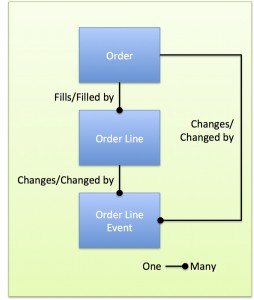

My fictionalized model illustrates this case’s anti-pattern. Say there’s an order management system tracking Orders, Order Lines, and “Order Line Events”, customer transactions involving an order item. The Order Line table includes a foreign key to the Order table. The Order Line Event table includes foreign keys to both the Order Line and the Order.

The latter relationship from Order Line Event to Order is logically unnecessary. Each Order line is related to exactly one Order, so if an Order Line Event relates to an Order Line it must also relate to a specific order.

Beyond being unnecessary, in this case the extra relationship turned out to be harmful. Somehow the online system had a bug that updated an Event’s relationship to a different Order than the related Order Lines. So a single Order Line Event could be related to two separate Orders, one through the Order Line and the other directly through the Changes/Changed By relationship.

In the real example there were some specific impacts that I won’t go into, but you can imagine the possibilities. Here are just three:

- Customer service representatives addressing customer complaints have invalid records of negative events

- Customer contact reporting and analysis is skewed

- Processes that purge old records may be unable to delete orders with mismatched foreign keys. Say you want to delete all data for Order 1. If an Order Line Event relates to both Order 1 and Order 2, the foreign key to Order 2 prevents delete of the Event unless Order 2 is also being deleted.

So, a database design that seems imperfect but “good enough” in fact isn’t. In this case it would have been well worth taking extra time during design to prevent the chance of subtle but significant errors in the application.