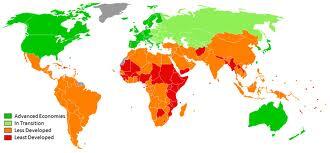

While commentators routinely discuss the opportunities for the United States and many other developed countries to use data and analytics to improve the lives of their citizens, the many opportunities for data to transform the developing world are less well-known.

While commentators routinely discuss the opportunities for the United States and many other developed countries to use data and analytics to improve the lives of their citizens, the many opportunities for data to transform the developing world are less well-known.

While commentators routinely discuss the opportunities for the United States and many other developed countries to use data and analytics to improve the lives of their citizens, the many opportunities for data to transform the developing world are less well-known. Projects spanning big and small data, from complex approaches like modeling disease diffusion to simple analyses enabled by newly open government data, have begun to crop up across developing countries and at international organizations such as the United Nations’ Global Pulse project, and they can help improve the quality of life in the developing world in at least four main areas: public health, public safety, government services, and agriculture.

While commentators routinely discuss the opportunities for the United States and many other developed countries to use data and analytics to improve the lives of their citizens, the many opportunities for data to transform the developing world are less well-known. Projects spanning big and small data, from complex approaches like modeling disease diffusion to simple analyses enabled by newly open government data, have begun to crop up across developing countries and at international organizations such as the United Nations’ Global Pulse project, and they can help improve the quality of life in the developing world in at least four main areas: public health, public safety, government services, and agriculture.

First, data can be used to keep people healthy. With the help of IBM, the city of Tshwane, South Africa piloted a crowdsourced app known as WaterWatchers that lets users report water supply information, such as faulty pipes, through SMS. As a result, IBM found that the city was losing almost $30 million in wasted water annually. A similar effort by Cipesa, a Kampala-based communications technology non-profit, allows journalists and citizens to monitor and document health services delivery in Northern Uganda with a mobile app, in order to identify discrepancies in official reports and drive infrastructure improvement efforts. Researchers have also demonstrated using techniques from network theory to find the source of disease outbreaks and other public health epidemics. Using a modeling technique originally developed to locate an individual phone from multiple cell tower signals, researchers from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland showed it was possible to trace the origin of a 2000 South African cholera outbreak. This would allow public health organizations and local authorities to identify at-risk populations for fure outbreaks. Although the technique is still new, there are other active efforts to model epidemics in Africa, such as those spearheaded by the South African Center for Epidemiological Modeling and Analysis. Other public health efforts use fingerprint sensors to track children’s’ vaccination histories, such as VaxTrac, a vaccination registry created by New Mexico-based biometric authentication company Lumidigm. Using that registry, which can be operated using low-cost mobile devices, doctors can access patients’ past vaccination histories reliably and securely to personalize care.

Second, data can be used to prevent crime and improve public safety. There have been a number of efforts to use data to forecast civil unrest, such as a team at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum mining Twitter data to anticipate political violence and a group at the University of Sydney using machine learning to predict mass atrocities. Researchers have also explored using remote sensing, such as a University of British Columbia study that used Google Earth images to identify illegal fishing structures on Iran’s Persian Gulf coast and estimate illicit fishing rates in the region. Perhaps the most widely deployed of data-driven efforts to promote public safety are crisis maps, which draw from a range of sources, including local citizen reports, remote volunteers’ map annotations, social network data, and environmental data, to aid emergency responders and journalists in times of natural disaster or war. Crisis maps have been deployed during dozens of events worldwide, including the 2012 Haiti earthquake and the 2010 Pakistan floods.

Third, data can improve government services. The World Bank’s Systems Approach to Better Education Results (SABER) program collects data on the policies and institutions of education systems around the world to encourage comparisons and identify where individual countries may be most in need of interventions. The bank is piloting the program in three Nigerian states and has identified several specific areas where education policies differed from global best practices, including poor teacher allocation and difficulty reporting budgetary problems to education authorities. The states’ governments have adopted some of the SABER recommendations and are currently working to implement the new policies. Another World Bank program in the Philippines targets public transit provisioning and urban congestion. The bank built a database of public transit data in Manila to help authorities map transit routes and identify gaps and overlaps, and developed a platform for local authorities to digitally track road accidents, which it will eventually map to help the local government identify dangerous areas and prioritize safety personnel. San Francisco-based startup Premise focuses on improving macroeconomic data quality to help inform government policies and economic development initiatives. The company scrapes price data online and collects it from city residents with a mobile app to create a consumer price index that is timelier than official sources. It has launched its partially crowdsourced consumer price index in several regions around the world, including India and parts of Africa and Southeast Asia.

Finally, data can help improve agriculture in countries with widespread food insecurity or where harvests are uncertain. The Grameen Foundation, a microfinance non-profit, partnered with the data analytics company Palantir in 2012 to analyze geo-located soil samples from Uganda and map the spread of crop and livestock blight. The groups hope their analysis can be extended to create an alert system for farmers who might be affected by such outbreaks in time for them to insure their holdings or take safety measures. Nairobi-based Gro Ventures is building a data platform for the African agriculture sector that integrates information on crops and environmental factors to improve credit models and give banks the confidence to lend to farmers. One of the company’s offerings based on the platform lets multiple farmers pool their data to apply for collective loans for shared tractors and other equipment.

A wide variety of initiatives already target public health, public safety, government services, and agriculture in the developing world, and data analytics will not replace them. Instead, data offers a means of making traditional efforts more efficient, as in the case of IBM’s crowdsourced water monitoring system that operated without the need (or expense) of a central inspection authority. Data analysis can also help draw attention to crucial development factors traditional efforts may have missed, as in the case of the World Bank’s education policy benchmarking system. Nontraditional data sources can help governments in developing countries supplement traditional data collection infrastructure, as in the case of the crisis mapping effort that draws from social media information to aid first responders during emergencies. In short, development groups should take note of the new opportunities data affords to help them do their jobs more effectively and efficiently and strive to integrate analytics to ensure better outcomes for the citizens of the countries they work with.

This post was originally published on the Center for Data Innovation website.